The replicas move through a succession of configurations called views. In a view one replica is the primary and the others are backups. Views are numbered consecutively. The primary of a view is replica p such that p = v mod |R|, where v is the view number. View changes are carried out when it appears that the primary has failed. Viewstamped Replication [26] and Paxos [18] used a similar approach to tolerate benign faults (as discussed in Section 8.)

The algorithm works roughly as follows:

The remainder of this section describes a simplified version of the algorithm. We omit discussion of how nodes recover from faults due to lack of space. We also omit details related to message retransmissions. Furthermore, we assume that message authentication is achieved using digital signatures rather than the more efficient scheme based on message authentication codes; Section 5 discusses this issue further. A detailed formalization of the algorithm using the I/O automaton model [21] is presented in [4].

Each message sent by the replicas to the client includes the current view number, allowing the client to track the view and hence the current primary. A client sends a request to what it believes is the current primary using a point-to-point message. The primary atomically multicasts the request to all the backups using the protocol described in the next section.

A replica sends the reply to the request directly to the client. The

reply has the form REPLY, v, t, c, i, r

,

where v is the

current view number, t is the timestamp of the corresponding request,

i is the replica number, and r is the result of executing the requested operation.

The client waits for f+1 replies with valid signatures from different replicas, and with the same t and r, before accepting the result r. This ensures that the result is valid, since at most f replicas can be faulty.

If the client does not receive replies soon enough, it broadcasts the request to all replicas. If the request has already been processed, the replicas simply re-send the reply; replicas remember the last reply message they sent to each client. Otherwise, if the replica is not the primary, it relays the request to the primary. If the primary does not multicast the request to the group, it will eventually be suspected to be faulty by enough replicas to cause a view change.

In this paper we assume that the client waits for one request to complete before sending the next one. But we can allow a client to make asynchronous requests, yet preserve ordering constraints on them.

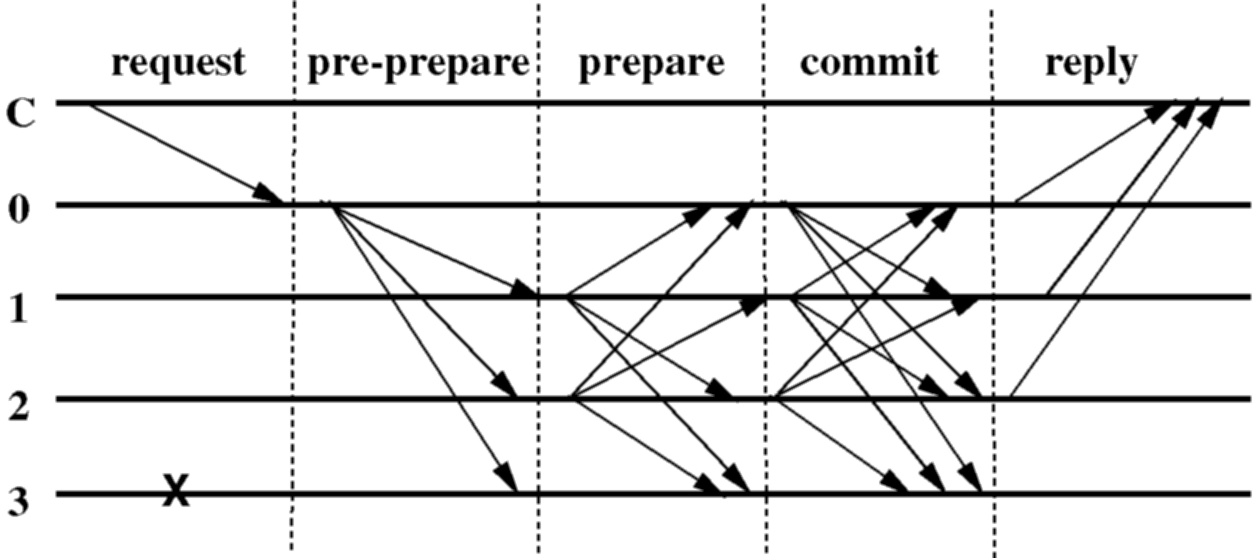

When the primary, p, receives a client request, m, it starts a three-phase protocol to atomically multicast the request to the replicas. The primary starts the protocol immediately unless the number of messages for which the protocol is in progress exceeds a given maximum. In this case, it buffers the request. Buffered requests are multicast later as a group to cut down on message traffic and CPU overheads under heavy load; this optimization is similar to a group commit in transactional systems [11]. For simplicity, we ignore this optimization in the description below.

The three phases are pre-prepare, prepare, and commit. The pre-prepare and prepare phases are used to totally order requests sent in the same view even when the primary, which proposes the ordering of requests, is faulty. The prepare and commit phases are used to ensure that requests that commit are totally ordered across views.

In the pre-prepare phase, the primary assigns a sequence number, n,

to the request, multicasts a pre-prepare message with m

piggybacked to all the backups, and appends the message to its log. The

message has the form

PRE-PREPARE, v, n, d

, m

,

where v indicates the view in which the message is being sent, m

is the client's request message, and d

is m's digest.

Requests are not included in pre-prepare messages to keep them small. This is important because pre-prepare messages are used as a proof that the request was assigned sequence number n in view v in view changes. Additionally, it decouples the protocol to totally order requests from the protocol to transmit the request to the replicas; allowing us to use a transport optimized for small messages for protocol messages and a transport optimized for large messages for large requests.

A backup accepts a pre-prepare message provided:

If backup i

accepts the PRE-PREPARE, v, n, d

, m

message, it enters the prepare phase by multicasting a

PREPARE, v, n, d, i

message to all other replicas and adds both messages to its log. Otherwise,

it does nothing.

A replica (including the primary) accepts prepare messages and adds them to its log provided their signatures are correct, their view number equals the replica's current view, and their sequence number is between h and H.

We define the predicate prepared(m, v, n, i) to be true if and only if replica i has inserted in its log: the request m, a pre-prepare for m in view v with sequence number n, and 2f prepares from different backups that match the pre-prepare. The replicas verify whether the prepares match the pre-prepare by checking that they have the same view, sequence number, and digest.

The pre-prepare and prepare phases of the algorithm guarantee that non-faulty

replicas agree on a total order for the requests within a view. More precisely,

they ensure the following invariant: if prepared(m, v, n, i)

is true then prepared(m', v, n, j)

is false for any non-faulty replica j

(including i = j)

and any m' such

that D(m')D(m). This

is true because prepared(m, v, n, i) and |R| = 3f+1

imply that

at least f+1 non-faulty

replicas have sent a pre-prepare or prepare for m

in view v with

sequence number n.

Thus, for prepared(m', v, n, j)

to be true at least one of these replicas needs to have sent two conflicting

prepares (or pre-prepares if it is the primary for v),

i.e., two prepares with the same view and sequence number and a different

digest. But this is not possible because the replica is not faulty. Finally,

our assumption about the strength of message digests ensures that the probability

that m

m' and D(m) = D(m')

is negligible.

Replica i

multicasts a COMMIT, v, n, D(m), i

to the other replicas when prepared(m, v, n, i)

becomes true. This starts the commit phase. Replicas accept commit messages

and insert them in their log provided they are properly signed, the view

number in the message is equal to the replica's current view, and the sequence

number is between h and H.

We define the committed and committed-local predicates as follows: committed(m, v, n) is true if and only if prepared(m, v, n, i) is true for all i in some set of f+1 non-faulty replicas; and committed-local(m, v, n, i) is true if and only if prepared(m, v, n, i) is true and i has accepted 2f+1 commits (possibly including its own) from different replicas that match the pre-prepare for m; a commit matches a pre-prepare if they have the same view, sequence number, and digest.

The commit phase ensures the following invariant: if committed-local(m, v, n, i) is true for some non-faulty i then committed(m, v, n) is true. This invariant and the view-change protocol described in Section 4.4 ensure that non-faulty replicas agree on the sequence numbers of requests that commit locally even if they commit in different views at each replica. Furthermore, it ensures that any request that commits locally at a non-faulty replica will commit at f+1 or more non-faulty replicas eventually.

Each replica i executes the operation requested by m after committed-local(m, v, n, i) is true and i's state reflects the sequential execution of all requests with lower sequence numbers. This ensures that all non-faulty replicas execute requests in the same order as required to provide the safety property. After executing the requested operation, replicas send a reply to the client. Replicas discard requests whose timestamp is lower than the timestamp in the last reply they sent to the client to guarantee exactly-once semantics.

We do not rely on ordered message delivery, and therefore it is possible for a replica to commit requests out of order. This does not matter since it keeps the pre-prepare, prepare, and commit messages logged until the corresponding request can be executed.

Figure 1 shows the operation of the algorithm in the normal case of no primary faults. Replica 0 is the primary, replica 3 is faulty, and C is the client.

This section discusses the mechanism used to discard messages from the log. For the safety condition to hold, messages must be kept in a replica's log until it knows that the requests they concern have been executed by at least f+1 non-faulty replicas and it can prove this to others in view changes. In addition, if some replica misses messages that were discarded by all non-faulty replicas, it will need to be brought up to date by transferring all or a portion of the service state. Therefore, replicas also need some proof that the state is correct.

Generating these proofs after executing every operation would be expensive. Instead, they are generated periodically, when a request with a sequence number divisible by some constant (e.g., 100) is executed. We will refer to the states produced by the execution of these requests as checkpoints and we will say that a checkpoint with a proof is a stable checkpoint.

A replica maintains several logical copies of the service state: the last stable checkpoint, zero or more checkpoints that are not stable, and a current state. Copy-on-write techniques can be used to reduce the space overhead to store the extra copies of the state, as discussed in Section 6.3.

The proof of correctness for a checkpoint is generated as follows. When

a replica i produces

a checkpoint, it multicasts a message

CHECKPOINT, n, d, i

to the other replicas, where n

is the sequence number of the last request whose execution is reflected

in the state and d

is the digest of the state. Each replica collects checkpoint messages in

its log until it has 2f+1

of them for sequence number n

with the same digest d

signed by different replicas (including possibly its own such message).

These 2f+1 messages

are the proof of correctness for the checkpoint.

A checkpoint with a proof becomes stable and the replica discards all pre-prepare, prepare, and commit messages with sequence number less than or equal to n from its log; it also discards all earlier checkpoints and checkpoint messages.

Computing the proofs is efficient because the digest can be computed using incremental cryptography [1] as discussed in Section 6.3, and proofs are generated rarely.

The checkpoint protocol is used to advance the low and high water marks (which limit what messages will be accepted). The low-water mark h is equal to the sequence number of the last stable checkpoint. The high water mark H = h + k, where k is big enough so that replicas do not stall waiting for a checkpoint to become stable. For example, if checkpoints are taken every 100 requests, k might be 200.

If the timer of backup i expires in view v,

the backup starts a view change to move the system to view v+1.

It stops accepting messages (other than checkpoint, view-change, and new-view

messages) and multicasts a

VIEW-CHANGE, v+1, n, C, P, i

message to all replicas. Here n

is the sequence number of the last stable checkpoint s

known to i, C

is a set of 2f+1

valid checkpoint messages proving the correctness of s,

and P is a set

containing a set Pm

for each request m

that prepared at i

with a sequence number higher than n.

Each set Pm contains

a valid pre-prepare message (without the corresponding client message)

and 2f matching,

valid prepare messages signed by different backups with the same view,

sequence number, and the digest of m.

When the primary p

of view v+1 receives 2f

valid view-change messages for view v+1

from other replicas, it multicasts a

NEW-VIEW, v+1, V, O

message to all other replicas, where V

is a set containing the valid view-change messages received by the primary

plus the view-change message for v+1

the primary sent (or would have sent), and O

is a set of pre-prepare messages (without the piggybacked request).

O is computed as follows:

A backup accepts a new-view message for view v+1 if it is signed properly, if the view-change messages it contains are valid for view v+1, and if the set O is correct; it verifies the correctness of O by performing a computation similar to the one used by the primary to create O. Then it adds the new information to its log as described for the primary, multicasts a prepare for each message in O to all the other replicas, adds these prepares to its log, and enters view v+1.

Thereafter, the protocol proceeds as described in Section 4.2. Replicas redo the protocol for messages between min-s and max-s but they avoid re-executing client requests (by using their stored information about the last reply sent to each client).

A replica may be missing some request message m or a stable checkpoint (since these are not sent in new-view messages.) It can obtain missing information from another replica. For example, replica i can obtain a missing checkpoint state s from one of the replicas whose checkpoint messages certified its correctness in V. Since f+1 of those replicas are correct, replica i will always obtain s or a later certified stable checkpoint. We can avoid sending the entire checkpoint by partitioning the state and stamping each partition with the sequence number of the last request that modified it. To bring a replica up to date, it is only necessary to send it the partitions where it is out of date, rather than the whole checkpoint.

In Section 4.2, we showed that

if prepared(m, v, n, i)

is true, prepared(m', v, n, j)

is false for any non-faulty replica j

(including i = j)

and any m' such

that D(m')D(m). This

implies that two non-faulty replicas agree on the sequence number of requests

that commit locally in the same view at the two replicas.

The view-change protocol ensures that non-faulty replicas also agree on the sequence number of requests that commit locally in different views at different replicas. A request m commits locally at a non-faulty replica with sequence number n in view v only if committed(m, v, n) is true. This means that there is a set R1 containing at least f+1 non-faulty replicas such that prepared(m, v, n, i) is true for every replica i in the set.

Non-faulty replicas will not accept a pre-prepare for view v' > v without having received a new-view message for v' (since only at that point do they enter the view). But any correct new-view message for view v' > v contains correct view-change messages from every replica i in a set R2 of 2f+1 replicas. Since there are 3f+1 replicas, R1 and R2 must intersect in at least one replica k that is not faulty. k's view-change message will ensure that the fact that m prepared in a previous view is propagated to subsequent views, unless the new-view message contains a view-change message with a stable checkpoint with a sequence number higher than n. In the first case, the algorithm redoes the three phases of the atomic multicast protocol for m with the same sequence number n and the new view number. This is important because it prevents any different request that was assigned the sequence number n in a previous view from ever committing. In the second case no replica in the new view will accept any message with sequence number lower than n. In either case, the replicas will agree on the request that commits locally with sequence number n.

First, to avoid starting a view change too soon, a replica that multicasts a view-change message for view v+1 waits for 2f+1 view-change messages for view v+1 and then starts its timer to expire after some time T. If the timer expires before it receives a valid new-view message for v+1 or before it executes a request in the new view that it had not executed previously, it starts the view change for view v+2 but this time it will wait 2T before starting a view change for view v+3.

Second, if a replica receives a set of f+1 valid view-change messages from other replicas for views greater than its current view, it sends a view-change message for the smallest view in the set, even if its timer has not expired; this prevents it from starting the next view change too late.

Third, faulty replicas are unable to impede progress by forcing frequent view changes. A faulty replica cannot cause a view change by sending a view-change message, because a view change will happen only if at least f+1 replicas send view-change messages, but it can cause a view change when it is the primary (by not sending messages or sending bad messages). However, because the primary of view v is the replica p such that p = v mod |R|, the primary cannot be faulty for more than f consecutive views.

These three techniques guarantee liveness unless message delays grow faster than the timeout period indefinitely, which is unlikely in a real system.

State machine replicas must be deterministic but many services involve some form of non-determinism. For example, the time-last-modified in NFS is set by reading the server's local clock; if this were done independently at each replica, the states of non-faulty replicas would diverge. Therefore, some mechanism to ensure that all replicas select the same value is needed. In general, the client cannot select the value because it does not have enough information; for example, it does not know how its request will be ordered relative to concurrent requests by other clients. Instead, the primary needs to select the value either independently or based on values provided by the backups.

If the primary selects the non-deterministic value independently, it concatenates the value with the associated request and executes the three phase protocol to ensure that non-faulty replicas agree on a sequence number for the request and value. This prevents a faulty primary from causing replica state to diverge by sending different values to different replicas. However, a faulty primary might send the same, incorrect, value to all replicas. Therefore, replicas must be able to decide deterministically whether the value is correct (and what to do if it is not) based only on the service state.

This protocol is adequate for most services (including NFS) but occasionally

replicas must participate in selecting the value to satisfy a service's

specification. This can be accomplished by adding an extra phase to the

protocol: the primary obtains authenticated values proposed by the backups,

concatenates 2f+1

of them with the associated request, and starts the three phase protocol

for the concatenated message. Replicas choose the value by a deterministic

computation on the 2f+1

values and their state, e.g., taking the median. The extra phase can be

optimized away in the common case. For example, if replicas need a value

that is ``close enough'' to that of their local clock, the extra phase

can be avoided when their clocks are synchronized within some delta.

Next: Optimizations

Up:Contents Previous: Service

Properties